Pathophysiology of Diabetic Retinopathy: The Old and the New

Article information

Abstract

Vision loss in diabetic retinopathy (DR) is ascribed primarily to retinal vascular abnormalities—including hyperpermeability, hypoperfusion, and neoangiogenesis—that eventually lead to anatomical and functional alterations in retinal neurons and glial cells. Recent advances in retinal imaging systems using optical coherence tomography technologies and pharmacological treatments using anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drugs and corticosteroids have revolutionized the clinical management of DR. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of DR are not fully determined, largely because hyperglycemic animal models only reproduce limited aspects of subclinical and early DR. Conversely, non-diabetic mouse models that represent the hallmark vascular disorders in DR, such as pericyte deficiency and retinal ischemia, have provided clues toward an understanding of the sequential events that are responsible for vision-impairing conditions. In this review, we summarize the clinical manifestations and treatment modalities of DR, discuss current and emerging concepts with regard to the pathophysiology of DR, and introduce perspectives on the development of new drugs, emphasizing the breakdown of the blood-retina barrier and retinal neovascularization.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the most common microvascular complication in diabetic patients, with a higher incidence in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus compared with type 2 diabetes mellitus [1]. Consistent with the increasing prevalence of diabetes in developed and developing nations, DR is the leading cause of vision loss globally in working middle-aged adults [23]. Based on the presence or absence of retinal neovascularization, DR can be classified clinically into non-proliferative (NPDR) and proliferative (PDR) forms [23]. In eyes with PDR, aberrant neovascularization following retinal ischemia causes vision-threatening vitreous hemorrhage and tractional retinal detachment. Further, diabetic macular edema (DME) affects central vision at any stage of DR. Among diabetic populations, the estimated prevalence of any form of DR is 34.6% (93 million worldwide), and those of PDR and DME are 6.96% and 6.81%, respectively [1].

A major risk factor for DR is sustained hyperglycemia, but hypertension, dyslipidemia, and pregnancy have also been implicated [123]. Notably, certain diabetic populations do not develop DR despite having these systemic risk factors, whereas good glycemic control might not necessarily eliminate the lifetime risk of DR [2]. These patterns indicate that additional factors, such as genetic susceptibility, are involved in the initiation and progression of DR. Thus, it is often difficult to predict the risk of DR in individual diabetic patients.

In the past decade, pharmacological therapies using anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drugs and corticosteroids have dramatically changed the clinical management of DR [23]. However, because of their limited efficacy and potential adverse effects, a comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiology of DR is urgently needed for the development of new drugs. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge and emerging concepts of the pathophysiology of DR that have been obtained from the clinic and basic research and introduce perspectives on the development of new drugs.

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

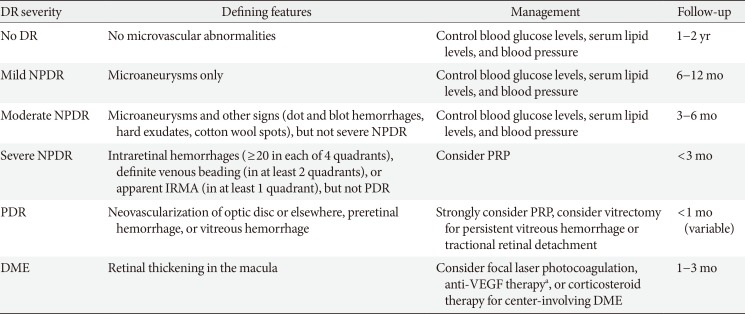

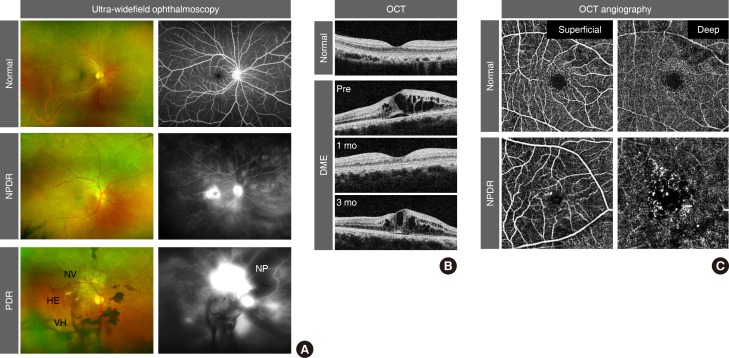

Because an early diagnosis of DR is crucial for preventing vision loss, routine ophthalmological examinations are recommended for all diabetic patients at severity-dependent intervals [23]. DR can be diagnosed ophthalmoscopically, based on retinal vascular lesions, such as microaneurysms, dot and blot hemorrhages, and deposition of exudative lipoproteins (hard exudates). Fluorescein angiography (FA), in conjunction with ultra-widefield scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, can reveal vascular leakage, non-perfusion, and neovascularization over the entire retina in DR (Fig. 1A). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) generates cross-sectional retinal images, enabling longitudinal assessments of the macular morphology and thickness in eyes with DME (Fig. 1B). In contrast to the potential risk of allergic reactions with FA, OCT angiography (OCTA) noninvasively generates high-resolution images of superficial and deep retinal vascular networks (Fig. 1C). Adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy can detect retinal hemorheological changes and cone photoreceptor irregularities in diabetic eyes [45]. Overall and local retinal functions can be evaluated by full-field and multifocal electroretinography (ERG), respectively [6]. These multimodal data might be able to be integrated by artificial intelligence-based systems in the future management of DR [7].

Clinical features of diabetic retinopathy (DR). (A) Pseudo-colored fundus (left) and fluorescein angiography (right) images from ultra-widefield ophthalmoscopy. Note the elevated leakage of fluorescein dye in the macular area in non-proliferative DR (NPDR) and from aberrant neovascularization (NV) in proliferative DR (PDR). Dark areas in fluorescein angiography represent vascular non-perfusion (NP). (B) Cross-sectional macular images from optical coherence tomography (OCT). Note the recurrence of diabetic macular edema (DME) at 3 months after intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injection. (C) Superficial and deep retinal vessel images from OCT angiography. Note the microaneurysms and enlargement of the foveal avascular zone in NPDR. HE, hard exudate; VH, vitreous hemorrhage.

Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Based on the severity of retinal vascular lesions, NPDR is categorized into mild, moderate, and severe forms (Table 1) [23]. Whereas mild NPDR exhibits only microaneurysms, moderate NPDR presents with additional signs of impaired vessel integrity and vessel occlusion, including dot and blot hemorrhages, hard exudates, and cotton wool spots. Severe NPDR is accompanied by more distinct features of retinal ischemia, such as venous beading and intra-retinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMAs) that are adjacent to non-perfusion areas.

For patients with mild to moderate NPDR, systemic control of hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia is critical in preventing the progression and reversing the severity of retinopathy [23]. However, if blood glucose levels decrease rapidly, the DR worsens in 10% to 20% of patients within 3 to 6 months [8]. For severe NPDR, panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) is considered for ablating ischemic neurons and glial cells in non-perfusion areas, thereby reducing their oxygen demand and production of pro-angiogenic growth factors, including VEGF [23]. Although PRP reduces the risk of progression to PDR, its destructive properties can cause peripheral visual field defects and reduced night vision [9]. Moreover, PRP often deteriorates central vision by exacerbating DME, which can be suppressed by adjunct sub-Tenon injections of triamcinolone acetonide, a potent long-acting corticosteroid [10].

Diabetic macular edema

By slit-lamp biomicroscopy or OCT, DME can be detected as retinal thickening in the macular areas, which is a consequence of the accumulation of fluid within neural tissues [111213]. Since the 1980s, DME had long been treated initially with focal lasers that targeted leaky microaneurysms and grid lasers that targeted macular areas of diffuse leakage and capillary non-perfusion [1415]. Today, intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy has become the standard of care for DME, based on a series of randomized controlled clinical trials that demonstrated its superiority in improving vision compared with laser therapy [23].

Bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech, San Francisco, CA, USA), a humanized monoclonal antibody against VEGFA, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for metastatic colorectal cancer in 2004 and has been used off-label for the treatment of DME [16]. Subsequently, intravitreal injections of ranibizumab (Lucentis; Genentech), the Fab fragment of a monoclonal anti-VEGFA, and aflibercept (Eylea; Regeneron, Tarrytown, NY, USA), a recombinant VEGF receptor (VEGFR) protein that neutralizes VEGFA, VEGFB, and placental growth factor (PlGF), were approved by the FDA for DME in 2012 and 2014, respectively [16]. The biological properties of VEGF signals are described below. Based on their anti-leakage and anti-angiogenic potency, intravitreal ranibizumab and aflibercept are used globally for DME, age-related macular degeneration, myopic choroidal neovascularization, and macular edema secondary to retinal vein occlusion, whereas off-label intravitreal bevacizumab is administered regionally because of its cost-effectiveness [1617]. In most cases, repeated intravitreal injections of these anti-VEGF agents are needed because of the recurrence of DME (Fig. 1B), which raises concerns over infectious endophthalmitis, cerebro-cardiovascular events, and a greater economic burden [18].

Intravitreal or sub-Tenon injections of triamcinolone acetonide and intravitreal implants of dexamethasone (Ozurdex; Allergan, Dublin, Ireland) and fluocinolone acetonide (Iluvien, Alimera Sciences, Alpharetta, GA, USA; and Retisert, Bausch & Lomb, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) are also used for DME, although the potential adverse effects of these corticosteroids, including cataract progression and elevations in intraocular pressure, should be monitored carefully [219]. Notably, corticosteroids are often effective for DME refractory to anti-VEGF therapies [19]. Based on their prolonged efficacy and cost-effectiveness, corticosteroids can be a useful option for DME, especially in eyes that have been implanted with intraocular lenses. In cases that experience unsuccessful outcomes with these pharmacological therapies, focal or grid laser remains an alternative therapy. Otherwise, vitrectomy surgery can be considered, particularly for DME that is associated with vitreomacular traction [20].

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

In eyes with PDR, new blood vessels that protrude from the ischemic retinal surface cause vitreous hemorrhages (Fig. 1A) [21]. In approximately 8% of PDR patients, the formation of contractile fibrovascular membranes accompanies aberrant neoangiogenesis, inducing tractional retinal detachment [22]. Persistent retinal hypoxia further leads to neovascularization of the iris and refractory glaucoma [21]. To avoid these devastating consequences, PRP should be applied immediately outside of the macular area [9]. For PDR eyes with sustained vitreous hemorrhage or tractional retinal detachment, vitrectomy should be performed in a timely manner [2].

Notably, repeated anti-VEGF injections for DME suppress the progression to PDR and mitigate the severity of PDR [2324]. Moreover, repeated anti-VEGF injections for PDR result in better visual acuity and lower rates of vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, and neovascular glaucoma compared with PRP [25262728]. These findings might prompt a shift in the clinical management of PDR, wherein treatment regimens that combine PRP, anti-VEGF agents, and corticosteroids should be optimized, depending on the ocular, systemic, and economic status of individual patients.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

To gain insights into the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie the pathophysiology of DR, diabetic mouse models are frequently employed because of their low maintenance cost and short reproductive cycle and the availability of genetically modified strains [29]. The structure and function of mouse retinas can be monitored longitudinally by ultra-widefield scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, OCT, OCTA, and ERG [293031]. Moreover, 2-photon and confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy, combined with a cataract-preventing contact lens in anesthetized mice, enables the in vivo imaging of retinal cell dynamics [32].

Type 1 diabetes mellitus mice, induced by β-cell destruction with streptozotocin (STZ) or by a spontaneous dominant-negative mutation in the insulin-2 gene (Akita mouse), recapitulate several features of early DR, including hyperpermeability and degeneration of retinal vessels [29]. However, these mice fail to reproduce any signs of advanced DR [29]. As alternative DR models, non-diabetic mice that overexpress or lack specific genes have been developed. For example, a transgenic mouse line that overexpresses insulin-like growth factor-1 develops retinal non-perfusion, IRMA, and neovascularization [33]. In addition, overexpression of VEGF and hyperglycemia in Akimba mice synergistically enhances the vascular abnormalities that are characteristic of DR [29]. With the recent advances in genomic engineering with CRISPR-Cas9 technology [34], mutant mouse models will expand our understanding of the causative roles of specific molecules in the pathophysiology of DR.

Hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, and inflammation

The metabolic abnormalities of diabetes induce the overproduction of mitochondrial superoxide in vascular endothelial cells (ECs), which subsequently leads to increased flux through the polyol pathway, the production of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), upregulation of the receptor for AGEs and its activating ligands, activation of the protein kinase C pathway, and overactivity of the hexosamine pathway [35]. These pathways elevate the levels of intracellular reactive oxygen species and cause irreversible cell damage through epigenetic changes, such as histone modifications, DNA methylation, and non-coding RNAs [3536]. Consistent with this concept of “metabolic/hyperglycemic memory,” euglycemic re-entry after transplantation of pancreatic islet cells to STZ-induced diabetic mice fails to heal retinal microvascular damage [37]. These findings might explain the effects of early glycemic control on the future development of DR [38].

Under sustained hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, various signaling pathways, and epigenetic modifications induce inflammation (Fig. 2) [353639]. The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and IL-6, are elevated in eyes with DR [40]. The pivotal functions of inflammation in the initiation and progression of DR have been corroborated empirically with the therapeutic efficacy of corticosteroids for DME and DR per se [41]. In diabetic retinas, the adhesion and infiltration of leukocytes might damage vascular ECs and neuroglial cells by physical occlusion of capillaries and through the release of inflammatory mediators and superoxide [42]. Thus, novel anti-inflammatory drugs with fewer adverse effects than corticosteroids are desired for the treatment of DR. To date, several compounds and antibody drugs that target inflammatory signals, such as MCP-1, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, have been evaluated clinically for DME or DR [1940], but none of them has been approved.

Schematic of key cellular and molecular events in the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Hyperglycemia initiates oxidative stress, epigenetic modifications, and inflammation in vascular endothelial cells (ECs). Neuroglial degeneration precedes microvascular changes. Pericyte loss from vessel walls sensitizes ECs to microenvironmental stimuli. Infiltrating macrophages secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A and placental growth factor (PlGF). A positive feedback loop between angiopoietin-2 (Ang2) and a forkhead box transcription factor, forkhead Box O1 (FOXO1), in ECs further destabilizes vessel integrity. These events form a cycle of vessel damage, leading to the breakdown of the blood-retina barrier. Retinal hypoxia resulting from vessel occlusion induces extra-retinal neoangiogenesis accompanied by fibrovascular membrane formation. Throughout these processes, signal transduction via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathways downstream of VEGF receptor (VEGFR) 2 in ECs is pivotal in retinal angiogenesis and vascular leakage. Tie2, tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like loops and epidermal growth factor homology domains 2.

Although it remains unknown why retinal microvascular abnormalities develop over years of hyperglycemic periods (more than 5 years in type 2 diabetes mellitus), clinical and experimental evidence has demonstrated irreversible loss of neurons preceding vascular lesions in diabetic retinas (Fig. 2) [43444546]. Thus, neuroprotective agents, such as eye drops of somatostatin or brimonidine (an α-2 adrenergic receptor agonist), are expected to prevent neuroglial degeneration and preserve long-term vision in subclinical and early DR (EUROCONDOR study [NCT01726075]) [4748].

Vascular endothelial growth factors

In 1948, Michaelson postulated the presence of a pro-angiogenic factor derived from hypoxic retinas in DR [49]. After the discovery of VEGF in the 1980s [5051], increased VEGF levels were reported in eyes with PDR in 1994 [52]. Then, VEGF injections into monkey eyes reproduced the retinal vascular abnormalities that were seen in NPDR and PDR [53]. Subsequently, extensive research on the physiological and pathological functions of VEGF led to the development of anti-VEGF drugs [16].

The VEGF family, comprising VEGFA, VEGFB, VEGFC, VEGFD, and PlGF, are secretory glycoprotein ligands, each of which binds distinctly to the transmembrane tyrosine kinases VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and VEGFR3 (Fig. 2) [5455]. VEGFA (herein referred to as VEGF unless otherwise noted) binds to VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, whereas VEGFB and PlGF bind only to VEGFR1 [5455]. VEGFC and VEGFD bind to VEGFR3 and regulate lymphangiogenesis, whereas proteolytic processing of these ligands allows binding to VEGFR2 [5455].

During hypoxia, VEGFA is upregulated transcriptionally, and alternative mRNA splicing generates several VEGFA isoforms, such as VEGFA121, VEGFA165, and VEGFA189, in human [545556]. These VEGFA isoforms have disparate binding affinities to extracellular matrices and a VEGFR2 co-receptor, neuropilin-1. Post-translational processing of VEGFA proteins further diversifies their distribution and signaling activities [54]. In vascular ECs, the binding of VEGFA to VEGFR2 activates several signal transduction cascades, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and the phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway, thereby promoting cell proliferation and migration and the subsequent formation of new blood vessels [5455]. Further, the VEGFA-VEGFR2 signal disrupts EC-EC adherens and tight junctions, leading to vascular hyperpermeability and fluid extravasation [5455]. Thus, the VEGFA-VEGFR2 signal is pivotal in retinal angiogenesis and vascular leakage in DR (Fig. 2) [4956].

In ECs, transmembrane and soluble VEGFR1 functions as a decoy for VEGFA, modulating the intensity of the VEGFR2 signal [5455]. The physiological functions of endothelial VEGFR1 signaling, activated by VEGFA, VEGFB, or PlGF, are assumed to be negligible, because mice that lack the intracellular kinase domain of VEGFR1 are viable and have no vascular abnormalities [57]. Conversely, the VEGFR1 signal in monocytes and macrophages contributes significantly under inflammatory conditions [58], correlating with the upregulation of VEGFB and PlGF in eyes with DR [59].

In contrast to its deleterious functions in pathological settings, VEGFA has been implicated in the maintenance of the homeostasis of neural retinas, in which a subset of neurons and Müller glia constitutively express VEGFR2 [60]. Furthermore, VEGFA that is secreted from retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells is indispensable for maintaining choroidal vessels [6162], raising concerns over the harmful effects of repeat anti-VEGF injections. Nonetheless, new anti-VEGF drugs are still being developed to prolong the potency and injection intervals in the treatment of DR. Among them, brolucizumab (RTH258), a humanized single-chain antibody fragment against VEGFA, is expected to reduce the injection frequency because of its small molecular weight and high intravitreal concentration [63]. Currently, the KITE (NCT03481660) and KESTREL (NCT03481634) phase 3 clinical trials are evaluating the efficacy and safety of brolucizumab for DME compared with aflibercept.

Angiopoietins

Angiopoietin-1 (Ang1) was identified as an agonistic ligand of endothelial tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like loops and epidermal growth factor homology domains 2 (Tie2) receptor in 1996 by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. [64]. The binding of Ang1 to Tie2 activates the PI3K/Akt pathway, leading to the phosphorylation and inactivation of a forkhead box transcription factor, forkhead box O1 (FOXO1), in ECs (Fig. 2). This signaling stabilizes vessel integrity by promoting EC survival, preventing vascular permeability, and suppressing inflammatory responses [65]. In 1997, Regeneron reported another ligand, Ang2, that binds Tie2 with similar affinity as Ang1 [66]. However, Ang2 weakly activates Tie2 in ECs. Thus, Ang2 was assumed to be a natural Tie2 antagonist that counteracts Ang1-mediated vessel stabilization.

Ang2 renders ECs more sensitive to pro-angiogenic, pro-permeable, and pro-inflammatory stimuli, such as VEGFA and TNF-α [65]. Moreover, Ang2 is upregulated by hypoxia, VEGFA, and hyperglycemia [6768], whereas Ang2-induced activation of FOXO1 upregulates Ang2, forming a positive feedback loop [65]. These findings indicate that Ang2 facilitates angiogenesis, vascular permeability, and inflammation under certain disease settings. Ang2 is upregulated in eyes with DR, age-related macular degeneration, and retinal vein occlusion [6970].

To date, a series of Ang2 blockers and Tie2 activators have been developed [71]. Among them, the Tie2 activator AKB-9778 [72], the anti-Ang2/VEGFA bispecific antibody RG7716 [69], and the fully human monoclonal anti-Ang2 nesvacumab (REGN910) [73] have been evaluated clinically for treating DR. The phase 2 RUBY study (NCT02712008) for DME reported no further improvement with the combination of aflibercept and nesvacumab compared with aflibercept alone. On the other hand, the phase 2 TIME-2 study (NCT02050828) of the combination of AKB-9778 and ranibizumab and the phase 2 BOULEVARD study (NCT02699450) of RG7716 reported favorable outcomes in the treatment of DME [74]. Notably, Ang2 can act as a Tie2 agonist, depending on the environment [7576]. Thus, anti-Ang2 drugs might inhibit the agonistic activity of Ang2 and result in unexpected outcomes.

Breakdown of the blood-retina barrier

To maintain retinal homeostasis, the leakage of plasma into neural tissues is regulated tightly by the inner and outer blood-retina barrier (BRB), sealed by retinal vascular ECs and RPE cells, respectively [111213]. Although dysfunction of the RPE can increase the influx of fluid from the underlying choroidal vessels in diabetic eyes, the pathogenic role of the breakdown of the outer BRB in DME is not fully understood [1112]. Conversely, elevated paracellular and transcellular leakage in retinal ECs causes the inner BRB to break down in DR [111213]. Based on the seminal histopathological observations of human diabetic eyes [77], the consensus is that pericyte dropout from retinal capillary walls is responsible for breakdown of the inner BRB (Fig. 2).

Retinal pericytes originate from the neural crest and regulate blood flow by providing mechanical strength to the vessel walls [78]. In addition, pericytes are pivotal in maintaining EC integrity via secretory signals and direct cell-cell contact [78]. In developing retinas, EC-derived platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) B promotes the recruitment of PDGF receptor (PDGFR) β-expressing pericytes to nascent blood vessels [78]. Therefore, disruptions in the PDGFB-PDGFRβ signal in postnatal mice can deplete pericytes from growing retinal vessels, leading to vessel enlargement, hyperpermeability, hypoperfusion, retinal edema, and hemorrhage [798081]. Notably, transient inhibition of pericyte recruitment during development results in persistent EC-pericyte dissociation in adult retinas, with vascular lesions that are characteristic of DR [81]. In pericyte-deficient retinas, the ECs of superficial retinal vessels proliferate actively but fail to migrate down into the deeper layers, forming aneurysm-like structures with excess accumulation of ECs [81]. In human DR, mitotic ECs are also found in microaneurysms [77], whereas microaneurysms occasionally disappear after intravitreal anti-VEGF injection [82]. These findings suggest that the formation of microaneurysms in DR is in part attributed to the over-proliferation of pericyte-deficient ECs in response to VEGFA.

In mouse retinas, a deficiency in pericytes induces endothelial inflammation and perivascular macrophage infiltration [8081]. In this setting, macrophage-derived VEGFA activates endothelial VEGFR2, whereas VEGFA and PlGF activate VEGFR1 in macrophages in an autocrine manner. Moreover, pericyte-free ECs upregulate Ang2 and undergo FOXO1 nuclear translocation, especially in microaneurysms, forming an Ang2-FOXO1-based positive feedback loop [8081]. These experimental results indicate that pericyte deficiency in growing retinal vessels elicits a cycle of damage due to EC-macrophage interactions, leading to sustained inflammation and irreversible breakdown of the BRB [83]. Unexpectedly, however, stripping pericytes from adult retinas sensitizes ECs to VEGFA but is insufficient to induce alterations in vessel structure and function [80]. Moreover, the PDGFB-PDGFRβ signal is dispensable for maintaining EC-pericyte associations in adult retinas [80]. Thus, further investigation is required to determine the causes and consequences of pericyte dropout in the pathophysiology of DR.

Retinal neovascularization

During development, intra-retinal growth of new blood vessels delivers oxygen to neural tissues efficiently [8485], in contrast to extra-retinal vascular outgrowth, which fails to resolve the tissue hypoxia in PDR (Fig. 2). Comparative analyses of physiological and pathological angiogenesis in mouse retinas have provided mechanistic insights into vessel guidance. In postnatal mouse retinas, the ECs of developing blood vessels migrate over the extracellular matrix scaffolds that are formed by the preexisting astrocyte network [848586]. Retinal astrocytes further establish the concentration gradients of matrix-binding VEGFA that is secreted by them or by neurons, promoting intra-retinal projections of endothelial filopodia from the sprouting vascular tips [87]. Concurrently, chemorepulsive signals, such as neuron-derived semaphorin 3E (Sema3E), which binds to endothelial PlexinD1 receptor, retract disoriented endothelial filopodia, thereby rectifying angiogenic directions [8889].

Conversely, in an oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) mouse model, retinal ischemia that follows vessel regression under hyperoxia (75% O2 from postnatal day 7 to 12) evokes centripetal vascular regrowth, which gives rise to extra-retinal vascular tufts [90]. In this setting, degenerative astrocytes fail to form extracellular fibronectin matrices, whereas retinal neurons, but not astrocytes, predominantly express VEGFA [88]. Thus, defective physical scaffolds for EC migration and disrupted spatial distribution of VEGFA proteins may be responsible for the extra-retinal neoangiogenesis. Notably, the ECs of extra-retinal vessels prominently express PlexinD1, and intravitreal Sema3E injections selectively suppress disoriented angiogenesis without affecting retinal vascular regeneration in the OIR model [88]. Given the decreased levels of aqueous Sema3E in human eyes with PDR [91], supplementation with intravitreal Sema3E should have clinical benefit in preventing aberrant neoangiogenesis. To facilitate vascular regeneration in ischemic retinas, new modalities that restore the pro-angiogenic activities of retinal astrocytes should be developed.

In the formation of fibrovascular membranes that are associated with extra-retinal neoangiogenesis, a series of pro-fibrotic signals, such as transforming growth factor β, PDGF, and connective tissue growth factor, have been implicated in the transdifferentiation, proliferation, and migration of myofibroblasts and their production of contractile matrix [2292]. Nevertheless, the origins of retinal myofibroblasts remain unknown in PDR [22]. Conversely, cell-fate mapping analyses in mouse models of fibrosis have demonstrated the potential of pericytes and perivascular mesenchymal cells to transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts in various tissues and organs [93]. Given the rapid development or progression of tractional retinal detachment after injections of anti-VEGF drugs into PDR eyes [94], it is postulated that the remaining pericytes after EC ablation from retinal neovascularization constitute a source of myofibroblasts, which should be validated experimentally in future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Complementary clinical and experimental evidence has increased our understanding of the pathophysiology of DR. However, the molecular backgrounds that are responsible for retinal vascular abnormalities may vary in individual eyes with DR, as evidenced by their differential responses to anti-VEGF drugs and corticosteroids. Moreover, a substantial question remains unanswere d as to why the retina is preferentially affected in diabetic patients. To determine the common and retina-specific mechanisms underlying diabetic microvascular complications, the broad areas of biomedical research, including ophthalmology, diabetology, neuroscience, immunology, and vascular biology, will need to be integrated. These efforts will optimize personalized medicine by combining drugs with distinct modes of action in the future treatment of DR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all previous and current members of the Uemura laboratory who contributed to the original studies cited in this review manuscript. This work was supported in part by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (16H05155), the Japan Science and Technology Agency CREST “Spontaneous pattern formation ex vivo,” and the Takeda Science Foundation to Akiyoshi Uemura. We thank Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.