Not Control but Conquest: Strategies for the Remission of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Article information

Abstract

A durable normoglycemic state was observed in several studies that treated type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients through metabolic surgery, intensive therapeutic intervention, or significant lifestyle modification, and it was confirmed that the functional β-cell mass was also restored to a normal level. Therefore, expert consensus introduced the concept of remission as a common term to express this phenomenon in 2009. Throughout this article, we introduce the recently updated consensus statement on the remission of T2DM in 2021 and share our perspective on the remission of diabetes. There is a need for more research on remission in Korea as well as in Western countries. Remission appears to be prompted by proactive treatment for hyperglycemia and significant weight loss prior to irreversible β-cell changes. T2DM is not a diagnosis for vulnerable individuals to helplessly accept. We attempt to explain how remission of T2DM can be achieved through a personalized approach. It may be necessary to change the concept of T2DM towards that of an urgent condition that requires rapid intervention rather than a chronic, progressive disease. We must grasp this paradigm shift in our understanding of T2DM for the benefit of our patients as endocrine experts.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is classified into type 1 and type 2 according to classical dichotomy. Unlike type 1 diabetes mellitus, which is the predominant cause of decreased insulin secretion due to pancreatic damage related to autoimmunity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has multiple causes, such as genetic and environmental factors [1]. Although genetic predisposition plays a role in the onset of T2DM, most cases develop after middle age, and associations with diet, lifestyle, and weight gain have been confirmed [2]. A progressive decline in β-cell function is observed in most T2DM patients [3]. More drugs are required over time [4], and irreversible complications can arise [5].

However, normalization of blood glucose levels can be achieved and sustained without therapeutic intervention in some patients [6], and this semipermanent improvement of diabetes is being observed more often with recently updated treatments [7,8]. A durable normoglycemic state was observed in a number of studies that treated T2DM patients through metabolic surgery, intensive therapeutic interventions or significant lifestyle modification [9-11]. It was confirmed that the functional β-cell mass was also restored to a normal level [12].

Therefore, expert consensus introduced the concept of remission as a common term to express this phenomenon in 2009 [13]. Throughout this article, we introduce the recently updated consensus statement on the remission of T2DM in 2021 [14] and share our perspective on diabetes remission.

CAN DIABETES BE CURED? DEFINITION OF REMISSION

Defining remission of T2DM is difficult. Unlike diseases that sometimes resolve completely and are classified as disease status versus healthy, diabetes is defined by hyperglycemia based on constantly changing blood glucose levels in the body that may be affected in the short term by temporary events such as drug effects, pregnancy, and acute illnesses [15-17].

Different expressions, such as cure, reversal, resolution, and remission, have been used in various studies to express “the occurrence of durable normoglycemia without antidiabetic medications,” which is confirmed after diabetes is diagnosed due to persistent hyperglycemia [18-20]. Therefore, a group of experts proposed expressing the state of postdiabetes as “remission” through a consensus meeting in 2009. In a consensus statement for 2021, the group explained that remission was adopted as a representative term to express the normalization of glycemic control according to the opinion that it can reflect the characteristics of susceptible individuals who may require continuous monitoring and support. The definitions and criteria for diabetic remission defined in 2009 and 2021 are presented in Table 1.

Remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus as defined by the consensus expert groups from the United States and Europe

In the initial consensus from 2009, partial remission and complete remission were diagnosed for prediabetes and normal blood glucose levels, respectively, and criteria subdivided into prolonged remission were presented when complete remission status was more than 5 years [13]. However, in the new consensus from 2021, remission was changed to a single diagnostic standard, and the classification of the period was removed considering the complexity and lack of evidence for the standards of blood glucose level and maintenance period [14].

As a diagnostic criterion, it was recommended to measure the glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level 3 months after the discontinuation of drug treatment [21], and remission was confirmed if the HbA1c level was found to be less than 6.5%. In clinical situations where HbA1c may not reflect blood glucose levels, fasting glucose or the 2-hour postprandial glucose of oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) can be used according to the diagnostic criteria for diabetes, but OGTT was described as an undesirable method due to the variability and complexity of the test. Since continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has been recently applied, it is recommended to use the estimated HbA1c level (eA1c) or a glucose management indicator on CGM [22].

This suggested definition is primarily based on expert opinion, and there is not much evidence on the frequency, durability, and long-term medical outcome of remission status. In particular, it is worth noting that remission does not mean complete resolution of diabetes, as the definition of diabetic remission includes temporary remission of hyperglycemia over several months. The remission of T2DM is an unknown field that requires continued attention.

STRATEGIES FOR THE REMISSION OF TYPE 2 DIABETES MELLITUS

The number of patients reaching remission was extremely low in the natural course of diabetes. In a cohort study of 25.6 million American adults who received standard medical therapy, 1.5% of patients reported normal glycemic control that could stop treatment, and prolonged normalization over 5 years was 0.007% [6]. However, it has been consistently reported that more than half of patients can achieve remission with recent treatment methods that induce active glycemic control and significant weight loss (Tables 2-4). New diabetes drugs with significant weight loss effects have recently been developed and are expected to help patients achieve remission of T2DM [23,24].

Remission rates of T2DM after intensive insulin therapy in newly diagnosed patients as confirmed by randomized clinical trials

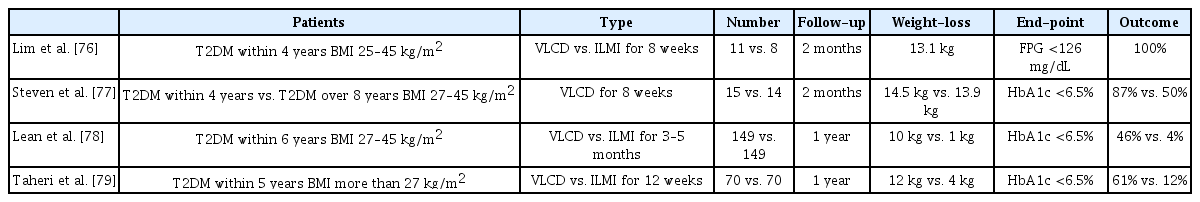

Remission rates of T2DM after a very-low-calorie diet in newly diagnosed patients as confirmed by randomized clinical trials

Metabolic surgery for patients with morbid obesity

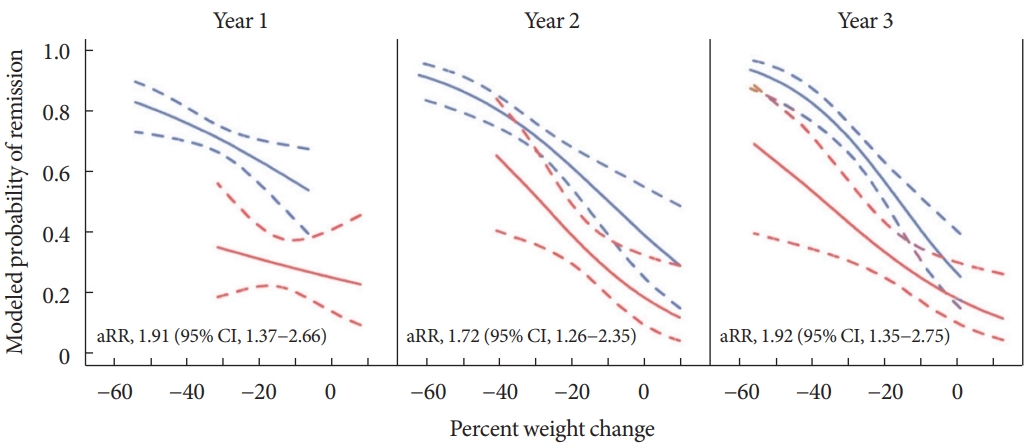

Surgical intervention increases satiety and decreases absorption by physically narrowing the path through which ingested food passes. In addition to weight loss, this method is accompanied by favorable effects on glycemic control including the threshold increment of incretin hormones caused by changes in intestinal structure [25,26]. Metabolic surgery has various forms, such as adjustable gastric band, vertical sleeve gastrectomy, and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). The effect may be different depending on the surgical method [27-29]. Diabetic remission was associated with postoperative weight loss, but subjects receiving RYGB were twice as likely to have diabetes remission than laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) even after adjusting for weight change (Fig. 1).

Modeled probabilities for diabetes remission according to weight loss in patients who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (red lines), and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (blue lines). Adjusted relative risk (aRR) estimates and 95% confidence intervals were adjusted for percent weight change and a propensity score based on baseline demographic and clinical variables associated with the type of surgery. Adapted from Purnell et al. [28], with permission from Oxford University Press.

The first rationale for remission was presented through metabolic, or bariatric surgery [30], and has been confirmed in a number of randomized clinical trials (Table 2) [31-38]. In a previous meta-analysis of 4,070 patients that included 19 observational studies for metabolic surgery, the overall T2DM remission rate after the surgery reached 78% [39]. In addition, a meta-analysis of clinical trials showed that bariatric surgery had better outcomes than the nonsurgical option. The effectiveness of surgical intervention is quick and definite [40]. However, permanent structural changes did not guarantee eternal effects. In some patients, weight regain occurred, and the improvement glycemic control may worsen again [41]. Additionally, surgical intervention is an invasive procedure that includes general anesthesia and can result in acute complications, including death [42]. Chronic complications, such as malnutrition and mental illness, are also commonly observed [43-45].

Therefore, experts recommend selective surgical treatment for patients with morbid obesity that cannot be easily controlled with routine pharmacologic approaches or patients with severe obesity with a body mass index higher than 30 to 35 kg/m2 [46,47]. Significant weight loss is necessary for fat loss of the visceral organs in terms of diabetes remission [48], and metabolic surgery may be an effective method that can induce sufficient and reliable weight loss for severely obese patients.

Intensive insulin therapy for newly diagnosed patients with severe hyperglycemia

Remission was observed in newly diagnosed patients with uncontrolled hyperglycemia following 2 to 3 weeks of intensive insulin therapy [49]. In subsequent studies, randomized clinical trials were performed to compare conventional treatment and different insulin treatment methods, and status was evaluated to determine whether remission was reached (Table 3, Fig. 2) [50-54]. Remission following intensive insulin therapy has been demonstrated to last more than 2 years, and it is believed that the shorter the time interval between diagnosis and intensive insulin therapy is, the greater the likelihood of remission [10]. β-cell conservation was also confirmed after intensive treatment early in the disease process [55,56]. Long-term effectiveness of glycemic control was observed in patients who received early combination therapy [57]. Improvement in β-cell function and long-term β-cell preservation was observed in patients treated with short-term intensive insulin therapy [58]. Therefore, early intervention for newly diagnosed T2DM patients is considered one of the strategies.

Effect of intensive insulin therapy for 2 weeks at initial rapid correction of hyperglycemia on diabetic remission at 1 year after the intervention in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adapted from Weng et al. [52], with permission from Elsevier. CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; MDI, multiple daily insulin injection; OHA, oral hypoglycemic agent.

The detrimental effects of hyperglycemia itself on β-cell function and insulin action are known [59], and it is established that the amount of time spent in hyperglycemic conditions increases the risk of complications [60-62]. Therefore, proactive treatment intensification has been proposed to minimize the cumulative effect of hyperglycemia. Since the pathogenesis of T2DM is complex, a synergistic effect between several drugs can be expected by using a combination therapy of drugs with various mechanisms. Early combined therapy can prevent delays in glycemic control due to clinical inertia that occurs during sequential intensification. The use of early combination therapy may be superior to reach optimal glycemic control quickly [63,64]. The significant impact of combination therapy in restoring β-cell function is receiving more attention with the development of new drugs [65].

However, indiscreet use of the initial intensive treatment may result in overtreatment of patients with borderline blood glucose levels, who may have otherwise maintained adequate glycemic control with lifestyle modifications or monotherapy. Combination therapy is expensive [66], and may increase the likelihood of side effects from taking multiple drugs [67]. Elderly patients may require a minimal approach, considering the correlation between hypoglycemia risk and life expectancy. Therefore, a personalized approach is needed because sequential approaches starting with minimal agents could be effective in some patients [68,69].

Intensive weight management with dietary calorie-restriction

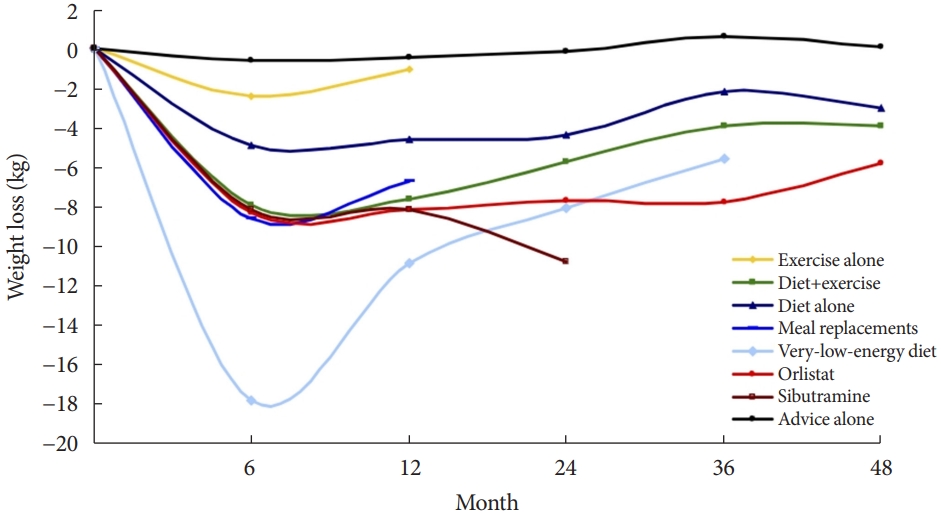

As a basic method to improve blood glucose control and reduce pancreatic β-cell burden, a lifestyle that reduces calorie intake and increases physical activity is recommended for all diabetic patients [70]. Among lifestyle modification strategies, the favorable effect of caloric restriction on glycemic control could be the most effective strategy in terms of both weight control and glycemic control [71-73]. In the meta-analysis of various weight loss methods, the very-low-calorie diet (VLCD) showed the most significant weight loss effect (Fig. 3).

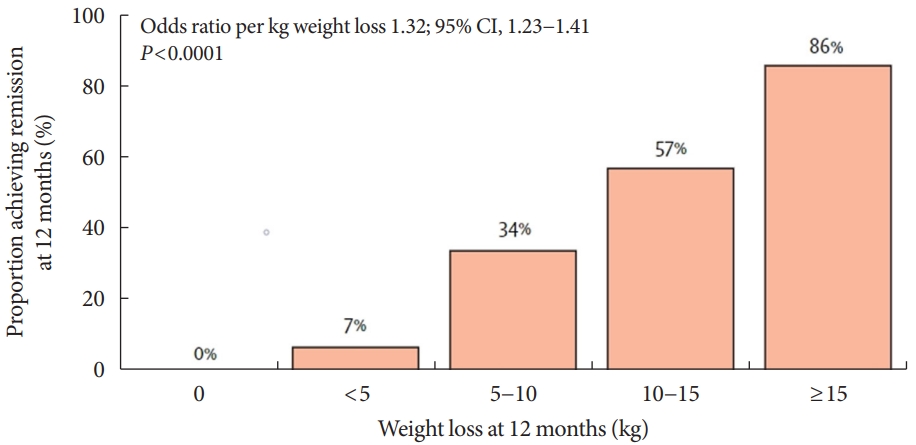

VLCD refers to a diet that contains 800 kcal or less per day with a relatively high protein-to-calorie ratio and with essential micronutrients. This diet is usually served in liquid form for 3 to 4 months [74]. Researchers considered the VLCD protocol as a therapeutic approach for obese diabetic patients [75]. Recent studies have also evaluated diabetes remission in these patients (Table 4) [76-79]. Lean et al. [78] combined VLCD with routine primary care and confirmed remission in 46% of study subjects. In the study subject group, the greater the weight loss was, the higher the remission rate, which is shown in Fig. 4.

Although VLCD is generally a safe method, it is recommended that it be performed under medical supervision. Fatigue and gastrointestinal disturbances may occur in the early stages [80,81], and sudden death with arrhythmia has been reported, although it is rare [82]. Currently, VLCD is not recommended for individuals with normal weight [83]. Previous researchers have suggested that preoperative VLCD application to patients with severe obesity planning metabolic surgery can reduce perioperative complications and maximize the effectiveness of surgery [84].

Development and clinical applications of new drugs

Recently, developed diabetes drugs have a unique mechanism, causing significant weight loss. For instance, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors act on the proximal convoluted tubule of the kidney to decrease glucose resorption in a way that induces glycosuria, and they have a glucose-lowering effect regardless of insulin secretion or insulin sensitivity [85]. This class of drugs can reduce weight and visceral fat because it is associated with urinary glucose excretion that causes caloric loss [86]. In a clinical trial using SGLT2 inhibitors in addition to basal insulin and metformin as an intensive intervention, the intervention group with SGLT2 inhibitors achieved more remission than compared to the conventional group (24.7% vs. 16.9%), and reduced the risk of diabetes recurrence by 43% [23].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP1) is a type of incretin hormone that acts in the intestines and inhibits glucagon secretion; various types of GLP1 receptor agonists (GLP1-RAs) have been developed and used [87]. Liraglutide, a type of GLP1-RA, has been studied to help preserve pancreatic β-cell function when used in early T2DM [88]. Recently, tirzepatide with higher potency has been developed and approved; it is a drug that exhibits dual action in both types of incretins, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP1 [89]. The drug resulted in a remission rate of 66% to 81%, depending on the drug dose over 52 weeks of use in a clinical study [90]. These drugs can produce rare hypoglycemic events and a large weight loss effect [91,92]. Therefore, we may consider these new medications rather than aggressive methods with known medical risks such as surgery, early intensive insulin therapy, and VLCD. However, as these drugs are relatively new methods, clear evidence for diabetes remission is lacking. Further studies are needed on the effects of new drugs on diabetes remission.

In addition, these newly developed drugs are unavailable for a small number of patients. SGLT2 inhibitors cannot be used for patients with chronic kidney disease, and it has been reported that they may cause ketoacidosis in more patients than conventional drugs [93]. Since GLP1-RAs and tirzepatide are injections, a psychological burden of patients is expected, and side effects such as local reactions at the injection site have been reported. Some patients discontinued the use of the drug due to gastrointestinal symptoms [94]. Moreover, these new drugs are expensive. Therefore, an approach that selects patients who may particularly benefit from this intervention may be necessary.

HOW DOES DIABETES REMISSION OCCUR? PATHOPHYSIOLOGY FOR DIABETES REMISSION

Dedifferentiation as a mechanism for degenerative changes in insulin-secreting β-cells

Predispositions that make individuals more susceptible to diabetes include genetic factors [95], the nutritional status of the prenatal period [96], and the environment in the early years of life [97]. β-Cells proliferate and secrete more insulin to adapt to the body’s increasing insulin requirements depending on the degree of weight gain [98]. However, β-cell failure eventually shows a progressive deterioration in which the drug demand gradually increases because of chronic hyperglycemia and overload related to weight gain [99]. Previously, it was explained that β-cells undergo apoptosis and progressively die in the worsening course of diabetes. However, as the concept of dedifferentiation is proposed and studies to support it are presented, it will become the basis for strategies to revitalize β-cells and restore function [100,101].

Hypothesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus as an intestinal disease

Rubino, a surgeon who specializes in metabolic surgery, describes diabetes as an operable intestinal disease, and he has paid attention to the improvement of diabetes and its mechanism after bariatric surgery [102]. Glycemic control improves rapidly within days of bariatric surgery, which occurs too quickly to account for weight loss alone [103]. Therefore, the structural change in the intestine was suggested as a mechanism for the improvement of blood glucose control. The change caused by food bypassing the proximal part of the small intestine is called the foregut hypothesis, and the change caused by food rapidly reaching the distal end of the small intestine is called the hindgut hypothesis [104]. The intestinal hormone—incretins play a major role in these changes, and the enteroinsular axis was first proposed in 1969 by Unger and Eisentraut [105] as a mechanism for the association between diabetes and intestinal hormones. They studied gut hormones secreted from intestines that are stimulated by food, particularly by carbohydrates and affect insulin secretion [106]. As a significant hormone associated with diabetes, in particular, GLP1 and GIP are two incretins thought to have a significant effect. Agonists for these hormones have also been developed as diabetes drugs and have shown significant effects, and remission studies for these drugs need to be continued.

Twin cycle hypothesis and personal fat threshold

Weight loss and consequent visceral fat loss are key for the remission of diabetes [107]. Some researchers have focused on the pathological role of fatty liver in T2DM in terms of energy balance and metabolic disturbances [108,109]. Fatty liver disease is caused by the storage of extra fat and improves in the early stage of weight loss [110]. Fat reduction according to weight loss varies depending on the body part, and it was reported that 16% of weight loss was accompanied by a 30% intra-abdominal fat reduction and 65% intrahepatic triglyceride loss [111,112]. In 2008, Taylor [20] proposed the twin cycle hypothesis, which posits that T2DM occurs because of a vicious cycle of fat accumulation in the liver and pancreas. Chronic excess energy causes fatty liver and an increase in lipids in systemic circulation if the liver overflows with fat. Fatty liver reduces insulin production and sensitivity and thus leads to a vicious cycle [113]. Finally, fat accumulates in the pancreas, leading to decreased β-cell function. He also proposed the concept of a personal fat threshold to explain the development of diabetes in individuals with relatively low body weight, which is supported by genetic studies associated with the capacity for subcutaneous fat storage [114,115]. Even in prediabetic patients who are of normal weight or slightly overweight who are not obese, weight loss may be helpful to prevent diabetes, which supports the personal fat threshold hypothesis [116].

TIME IS OUTCOME? PREDICTORS OF DIABETES REMISSION

Because the induction of remission results in relatively drastic changes in the body, selecting the target group and timing of intervention can be crucial points of discussion. Since some individuals have reached remission status after metabolic surgery, an assessment tool has been developed to predict the outcomes of these patients before surgery, and these models are primarily based on whether β-cell function is conserved (c-peptide), the degree to control of diabetes (HbA1c), the severity of diabetes (number of antidiabetic drugs and insulin use), and the duration of diabetes [117-122]. To increase the predictive power, a method that considers the demographics, surgical methods, and comorbidities has also been proposed [123], and recently, attempts have been made to make predictions easier through biochemical biomarkers [124].

In studies based on metabolic surgery and VLCD, it was reported that younger patients were more likely to reach remission [125]. In addition, the study that enrolled younger patients [77] reported higher remission rates (remission rate at 1 year: 61% vs. 46%) than the study [78] involving relatively older patients (average age of study subjects: 41.9 years vs. 52.9 years). However, in a cohort study in which patients received conventional medical therapy, remission was reported to have a higher prevalence in elderly patients. The remission in the total population was 1.5% [6], whereas the remission in the study targeting the population over 65 years old was 5% [126]. Although weight-based intervention appears to be more effective for patients at a younger age, diabetes in older adults may be more likely to “disappear” in terms of genetic susceptibility and exposure to drugs that can cause diabetes.

If diabetes is present for a long period of time, patients’ metabolic profiles are less likely to respond to weight changes [125]. The duration of diabetes was an important predictor of remission, which has been consistently reported in several studies [6,117,119,122,127,128]. Most patients treated with multiple antidiabetic drugs could not achieve remission even after significant weight loss following bariatric surgery due to irreversible β-cell damage [129]. In particular, insulin treatment appears to be significant in relation to the severity of diabetes and the degree of preservation of β-cell function [6,118,120-122].

In summary, factors such as the degree of glycemic control, whether insulin is needed and disease characteristics such as the duration of illness are considered to be significant factors rather than patient factors such as the patient’s age, sex, or BMI. In particular, the most important factor to reach remission may be early intervention for newly diagnosed diabetic patients. As with all diseases, early screening and active early treatment are thought to help improve the prognosis for diabetes.

DOES DIABETES REMISSION PERSIST? THE STORY AFTER REMISSION

Individuals who have previously been diagnosed with diabetes are more susceptible to diabetes than other individuals and have a higher risk of relapse. Researchers believe that weight loss and maintenance are key to maintaining remission of T2DM [115,130]. Sometimes the body resists changes following significant weight loss, and weight is easily regained [131]. To form and maintain a healthy lifestyle and to maintain longterm remission of diabetes, the patient’s own will is important, but the cooperation and support of family members, partners, acquaintances, and members of society is essential [132].

In addition, hyperglycemia appears to continue to affect the body even after it has improved, as the long-term consequences for hyperglycemic conditions, are referred to as the “metabolic memory” or “legacy effect” [133]. This effect is mainly associated with microvascular complications rather than effects on macrovascular complications or survival [134]. It is thought that individuals liberated from hyperglycemia will require continuous surveillance for recurrence and complications even after remission is confirmed.

UNMET NEEDS

Validation of remission definitions

The current definition of remission was determined by expert opinion based on the diagnostic criteria for diabetes, and new criteria (including the duration of maintaining remission) or different glucose standards may have to be considered. It may be necessary to lower the cutoff to reduce the risk of recurrence. The consensus of 2021 states that CGM-derived data can be used, but only the eA1c level is presented among the values. The data could be considered a novel metric, such as time in range (TIR), in the evaluation of remission.

Postdiabetes surveillance

The consensus recommends that patients with a history of diabetes after remission should undergo testing for glycemic status and complications related to diabetes at 1-year intervals. This is based on reported metabolic memory that is the lasting effect of previous hyperglycemic status despite improved glycemic control [135,136]. Through study of the long-term medical outcomes of patients following remission, how the monitoring cycle should be carried out and which procedures should be used to check for complications can be the subject of additional discussion.

Social intervention

With regard to the increase in the incidence of T2DM along with the prevalence of obesity, obesity may be not only a personal problem but also a social burden [137]. Therefore, obesity and related diseases are clearly fields that require intervention from the perspective of public health [138]. From the viewpoint of reducing the incidence of diabetes and the burden of medical expenses, the chronic disease management model for diabetes needs to be changed to a social intervention model for obesity [112], such as one that includes health campaigns for the general population and sugar taxes on food [139,140].

Studies for Korean ethnicity

T2DM occurs at an earlier age in Asian populations than in other races. The Asian population shows reduced insulin secretion, low weight tendencies, and many complications [141]. In terms of remission evaluation according to each treatment method, there are relatively few studies conducted in the Asian population, especially for Koreans. Therefore, there is a need for more research on remission in Korea as well as in Western countries.

CONCLUSIONS

Remission appears to be induced by intensive glycemic control and significant lifestyle change prior to irreversible β-cell changes [142,143]. By implementing short-term intensive insulin therapy in patients with uncontrolled hyperglycemia at an early stage of the disease, β-cell function improves, and remission of T2DM can be secured for a considerable period. In patients who are overweight at the initial stage of diagnosis, remission can be reached in more than half of patients if significant weight loss is induced by methods such as metabolic surgery or VLCD. New drugs, such SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP1-RAs, have a weight loss effect, so they can help to achieve this remission goal in a safer way (Fig. 5). Intensive glycemic control in T2DM increases the likelihood of remission at the earlier stage of the disease and helps to reduce the complications associated with T2DM even if remission is not achieved [144,145]. However, we should be wary of the side effects that accompany these methods, which cause dramatic changes in the body. From the perspective of long-term survival, it is necessary to pay attention to the risk of hypoglycemia in elderly patients, and additional research is needed on the long-term medical outcomes of diabetic remission [146,147]. Patients who have previously been diagnosed with diabetes are exposed to the risks of diabetes-related complications, even in patients who have improved and confirmed remission. Support and continuous medical supervision from family members, friends and medical staff are essential so that they can maintain a healthy lifestyle and screen for comorbidities associated with diabetes. T2DM is not a fate for individuals to helplessly accept. We have discussed the remission of T2DM, which can be achieved through a personalized approach. It may be necessary to change the concept of T2DM towards that of an urgent condition that requires rapid intervention rather than a chronic, progressive disease. We must grasp this paradigm shift in our understanding of T2DM for the benefit of our patients as endocrine experts.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2021R1A2C2013890).

Acknowledgements

We thank the copyright holders who gave permission to the figures of this article.